An examination of the radical overreach of proposed religious exemptions permitting discrimination on the basis of gender, gender identity, sexuality, and reproductive choices, as well as race, national origin, and religion in violation of the United States Constitution and domestic and international law

Discrimination in the Guise of Liberty:

Legal Analysis of Trump’s Draft Executive Order on “Religious Freedom”

Download this as a PDF.

Overview

On February 1, 2017, The Nation published a leaked version of an executive order reportedly being considered by the Trump administration that would expand religious liberty protections even beyond the substantial array of religious accommodations and exemptions accorded under existing law.[1] The Draft Executive Order, entitled “Establishing a Government-Wide Initiative to Respect Religious Freedom,” represents the latest effort by elements of the Christian right who are now emboldened in power to legitimize and immunize discrimination carried out under the guise of religious freedom, both domestically and abroad.[2]

On the domestic front, the current Draft Order arises directly out of long-running initiatives at the state and federal level[3] to statutorily elevate (and distort) the protection of the First Amendment’s free exercise clause above and beyond what is constitutionally required, generally with the aim of legitimizing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, or limiting access to abortion or contraception. This Draft Order would serve as an omnibus edict, bringing into play multiple items on the religious right’s agenda, including attacks on LGBTQ equality and rights, gender equality, reproductive rights, even prohibitions against race discrimination in the context of public accommodations, and separation of church and state.[4]

While several provisions clearly target same-sex marriage, gender identity, and the exercise of reproductive rights, other provisions would create special federal immunity from liability for discrimination on virtually any basis – including race, national origin, and religion – and by virtually anyone or any thing, as it expands the scope of who can claim religious exemptions to include corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and even joint stock companies, with no religious purpose. The Order would allow for the flouting of any number of generally applicable laws, if such actions or inactions are claimed to be motivated by a sincerely held religious belief or conscience. It would also immunize speech that could constitute workplace harassment or harassment in the spheres of education or housing, and undermine enforcement of laws prohibiting identity-based violence.

In addition to placing religious liberty in a realm of its own and creating an unconstitutional hierarchy of rights and people, the Draft Order also flunks the test set out by the Supreme Court to determine violations of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.[5] The Draft Order clearly violates the Establishment Clause as it represents an unmitigated, thoroughgoing, and excessive entanglement with religion, “establishes an official preference for certain religious beliefs over others,”[6] and improperly endorses, or seems to endorse, particular religious beliefs. In challenges to similar language included in state legislation, courts have found that it violated non-endorsement principles since “the State has put its thumb on the scale to favor some religious beliefs over others.”[7] The applicable test in these cases is whether, in light of the context and history of the relevant law or action, a reasonable observer would perceive a state endorsement of religion.[8] If so, such law or action amounts to a violation of the Establishment Clause. For example, if a mail carrier explicitly refused to deliver invitations for a same-sex couple’s wedding because of his religious beliefs—a belief that would be granted special immunity by the Draft Order—this could cause a reasonable person to think that the government has endorsed the religious grounds for such opposition.[9]

Attempting to cast these provisions as necessary to the protection of religious freedom, the Draft Executive Order radically overreaches by transforming the First Amendment’s guarantee of religious liberty from a flexible rule that embodies respect for religious diversity to an uncompromising trump card playable by anyone who wants to avoid compliance with any law they claim to find religiously or morally objectionable. The sheer scope of this over-accommodation of religion will result in the evisceration of a range of legal protections necessary to uphold equal protection under the law, leaving untold numbers of people more vulnerable to and defenseless against discrimination.

Working abroad, elements of the Christian right have also sought to entrench and give legal cover to severe discrimination against vulnerable LGBTQ communities, with some going so far as to push for laws that criminalize speech and advocacy in support of LGBTQ rights with long sentences of imprisonment.[10] Since Nuremberg, targeting a group for severe deprivation of basic, fundamental rights in a widespread or systematic manner constitutes the crime against humanity of persecution, one of the most serious violations of international law.[11] One international tribunal has explained that persecution is considered “one of the most vicious of all crimes against humanity” because it “nourishes its roots in the negation of the principle of equality of human beings.”[12] The Draft Order aims to make the same kind of widespread, systematic group-based persecution a part of official U.S. government policy, in violation of international law, as well as the U.S. Constitution.

Key Provisions

Section 1

Section 1 declares religious liberty to be a “fundamental natural right,” which is essentially a dog whistle to the religious right to affirm the view that religious liberty trumps all other civil rights in the constitution or federal law. Or, as one leading proponent of similar initiatives recently stated: “The church predates government… This goes back to the apostles … who said, ‘Look, you’re not gonna regulate what we say. We’re accountable to God, not to some government bureaucrat.’”[13] Kentucky Clerk Kim Davis relied on a similar notion of the supremacy of religious over secular law when she refused to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the Supreme Court’s Obergefell ruling because these marriages were “not valid in God’s eyes.”[14]

This section of the Order also declares as federal policy a level of deference to religious belief and exercise that far exceeds the parameters of the constitution historically deemed necessary for properly balancing and protecting the full array and interplay of constitutional rights.The purpose and effect of this Draft Order is to exempt all persons—defined very broadly—from otherwise neutral laws of general applicability that conflict with their religious beliefs or conscience. This absolute right to disobey the law because of one’s personal religious preferences or moral convictions, regardless of the consequence on others, is emphatically not required or sanctioned by First Amendment doctrine.

For well over a century, the Supreme Court has held that religious freedom does not provide an unconditional right to act in accordance with one’s beliefs, religious, moral, or otherwise. In 1990 in Employment Division v. Smith, Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the Court, summed up this longstanding principle, stating that the Supreme Court had “never held that an individual's religious beliefs excuse him from compliance with an otherwise valid law prohibiting conduct that the State is free to regulate.” To be sure, the Constitution requires the provision of religious exemptions in some circumstances, but that right is not absolute. Even in the pre-Smith case most favorable to religious exemptions, Wisconsin v. Yoder, the Court clearly stated that the “activities of individuals, even when religiously based, are often subject to regulation by the States in the exercise of their undoubted power to promote the health, safety, and general welfare, or the Federal Government in the exercise of its delegated powers.”[15]

In 1993, Congress passed the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), creating a more expansive statutory right to religious liberty than that provided by the First Amendment.[16] Even RFRA’s generous language accommodating sincerely held religious beliefs recognizes that religious liberty must be balanced against other important rights and government interests.

The Draft Order would make it a federal policy not to “coerce” in any way activities that violate the conscience of “Americans” and “religious organizations,” presumably even if those activities are required by generally applicable laws and are necessary to respect and protect the fundamental rights and dignity of others. If this had been the standard in 1983, the Internal Revenue Service likely could not have taken adverse action against Bob Jones University, which enjoyed tax exempt status, for its racially discriminatory policies prohibiting interracial marriage and dating based on a belief that the Bible prohibits such conduct. In Bob Jones University v. United States,the Supreme Court held the government had a “fundamental, overriding interest in eradicating racial discrimination in education.”[17]

Section 2

Section 2 provides for an extremely broad range of persons and entities covered by the order’s protections. By linking to the definition of “person” in 1 USC § 1, those covered by this religious liberty shield would include “corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals.” Beyond that, the definition of “religious organization” in subparagraph (c) is loosely defined and is also to be construed broadly. The broad extension of the entities covered by the Draft Order dramatically extends the potential sweep of discrimination to virtually all facets of life.

“Religious exercise” is defined to include acts, or refusals to act, motivated by sincerely held religious belief, “whether or not the act is required or compelled by, or central to, a system of religious belief” in line with the way the definition of that term was expanded and amended into the federal RFRA in 2000.

Section 3

Section 3 explicitly places the obligations of the Draft Order on all departments and agencies. Subparagraph (b) incorporates a position long espoused by the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and other like-minded groups under a misreading of RFRA.[18] That position would require the federal government to provide public funding to religious organizations even when those organizations refuse to perform key aspects of the programs funded with public money (such as provide services to LGBT people, to unmarried mothers, or to provide contraceptives and other reproductive health care to the intended beneficiaries of federal programs). The radical deference to and support for religion contained in the Draft Order would render the federal government an instrument and funder of religion.[19]

Section 4

Section 4(a), applied to persons as defined in 1 USC §1, would exempt “corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals” and “religious organizations” from complying with the contraceptive mandate for religious ormoral reasons. This extends exemptions to entities beyond those recognized in the Supreme Court’s controversial 2014 opinion in Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc.,[20] which, while extending religious belief for the first time to a for-profit corporation, limited its ruling to closely held corporations. With respect to cases involving religious institutions, like Zubik v. Burwell,[21] the order would appear to render these ongoing cases moot, since the heads of Health and Human Services, Labor, and Treasury, are required to issue an interim final rule extending the exemptions well beyond such religious institutions.

Section 4(b) overrides, or preempts, state laws that mandate contraceptive coverage by health insurers, which currently includes 28 states.[22] This section also responds to a case where a legislator objected to buying a health plan that included contraceptive coverage.[23]

Section 4(c) allows religious organizations (again, to be construed broadly “to encompass any organization, including closely held for-profit corporations, operated for a religious purpose, even if its purpose is not exclusively religious…”) involved in child-welfare services, including adoption, foster care, or family support services, etc., to discriminate on any basis, including race or religion, “due to a conflict with the organization’s religious beliefs.” For instance, a Christian religious organization could decline to provide, facilitate, or refer services to Muslim or Jewish families based on a “moral conflict” with their beliefs. So too, a faith-based adoption agency could refuse to place children with an interracial couple if their faith included teaching that condemned modern-day miscegenation. Beyond denying services for discriminatory reasons, the language is so-open ended, a religious organization could decline to perform services or aspects thereof, fail or refuse to comply with other generally applicable rules and regulations governing child-welfare and can claim such action or inaction is rooted in a “moral conflict.”

Section 4(d) dramatically widens the circle of those who can claim exemptions from existing law governing federal contracts and grants. Currently, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provides exemptions for a “religious corporation, association, educational institution, or society with respect to the employment of individuals of a particular religion to perform work connected with the carrying on by such corporation, association, educational institution, or society of its activities”[24] The Americans with Disabilities Act allows a “religious corporation, association, educational institution, or society” to give preference to individuals of a “particular religion to perform work connected with the carrying on by such corporation, association, education institution, or society of its activities,” even allowing that the religious organization “may require that all applicants and employees conform to the religious tenets of such organization.”[25]

By incorporating “person” and “religious organization” as defined elsewhere in the order, the provision would allow even non-religious “corporations, companies, associations, firms, partnerships, societies, and joint stock companies, as well as individuals,” receiving federal contracts, grants, or funds, to claim religious liberty exemptions from anti-discrimination law for otherwise discriminatory employment policies and practices. For example, a corporation could fire an employee for not conforming to its “religious tenets” for having an abortion or using contraception, or becoming pregnant while unmarried, or because of their sexual orientation.

Section 4(e) incorporates and expands upon provisions of the proposed First Amendment Defense Act, legislation that has been introduced in Congress several times and which singled out for special immunities those who hold religious or moral views that marriage is a union of one man and one woman and condemn sex outside marriage.[26] The Draft Order goes further in protecting a discriminatory view of gender identity, and that life begins at conception. During his campaign, in a press release entitled, “Issues of Importance to Catholics,” Donald Trump pledged to support the legislation if Congress made it a priority.[27] This section would also grant special rights to organizations speaking or advocating “from a religious perspective” while not granting similar protections to organizations speaking from a secular perspective, thus violating well-established Supreme Court precedent as a subsidy to religion in violation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause.[28]

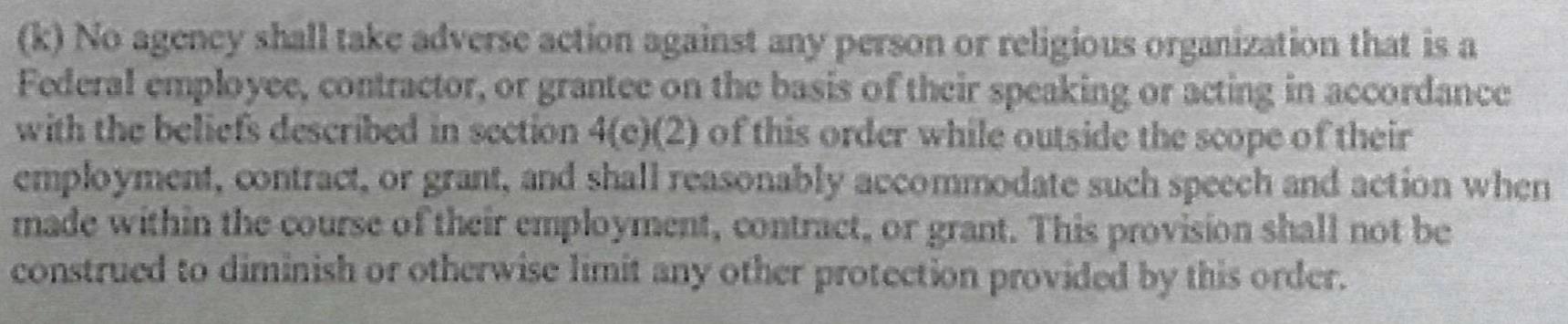

Section 4(k). This provision also has the effect of creating a set of special protections privileging speech and conduct in opposition to same-sex marriage, sex outside of marriage, transgender identity, and abortion and contraception, above speech on other issues. The provision would further undermine enforcement of laws prohibiting discrimination, harassment, and violence on the basis of race, sex, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, and gender identity in the workplace, housing, education, and credit. At the same time, given the Order’s license to discriminate generally, combined with this particular provision privileging certain speech, nonreligious people who speak their minds outside the workplace, as well as religious individuals who speak out in opposition to other issues – e.g., the administration’s actions on immigration – are rendered more vulnerable with less protection for their speech and beliefs.

Section 5

Section 5(a-b). These provisions halt any agency rulings, directives, or actions inconsistent with the order and would nullify previous executive orders. This includes executive orders issued by President Obama mandating non-discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity among federal contractors, which the current administration had announced on January 30, 2017 it would let stand.[29]

# # #

[1] Sarah Posner, Leaked Draft of Trump’s Religious Freedom Order Reveals Sweeping Plans to Legalize Discrimination, The Nation, February 1, 2007. https://www.thenation.com/article/leaked-draft-of-trumps-religious-freedom-order-reveals-sweeping-plans-to-legalize-discrimination/

[2] For information about the Christian right’s domestic strategies, see Frederick Clarkson, When Exemption Is the Rule: The Religious Freedom Strategy of the Christian Right, Political Research Associates, January 2016, http://www.politicalresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2016/01/When-Exemption-is-the-Rule-PRA-Report.pdf. For information about the work and impact of the Christian right abroad, see Kapya Kaoma, Globalizing the Culture Wars: U.S. Conservatives, African Churches & Homophobia, Political Research Associates, http://www.politicalresearch.org/2009/12/01/globalizing-the-culture-wars-u-s-conservatives-african-churches-homophobia/#sthash.tFBWiP7A.dpbs. See also, Jeff Sharlet, C Street: The Fundamentalist Threat to American Democracy, Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2010.

[3] For an overview of recent religious exemption legislation, see Memorandum from thePublic Rights/Private Conscience Project to Interested Parties, State & Federal Religious Accommodation Bills: Overview of the 2015-2016 Legislative Session, September 20, 2016, available at http://www.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/gender-sexuality/prpcp_exemption_overview_-_9.20.16.pdf.

[4] Religious Freedom: Protecting How We Practice Our Faith, Focus on the Family (November 2016) p. 11, http://www.focusonthefamily.com/socialissues/how-to-get-involved/are-you-concerned-about-the-future-of-religious-freedom.

[5] See Lemon v. Kurtzman, 403 U.S. 602 (1970); Santa Fe Independent School District v. Jane Doe, 530 U.S. 290, 314 (2000).

[6] Barber v. Bryant, No. 3:16-CV-417-CWR-LRA at 47 (S.D. Miss. June 30, 2016) (order granting preliminary injunction). In evaluating a law very similar to FADA, the Mississippi district court found that “On its face, [the bill] constitutes an official preference for certain religious tenets. If … specific beliefs are ‘protected by this act,’ it follows that every other religious belief a citizen holds is not protected by the act.” Id. at 48.

[7] Id. at 2.

[8] See Corporation of the Presiding Bishop v. Amos, 483 U.S. 327, 348 (1987) (O’Connor, J., concurring) (“To ascertain whether the statute conveys a message of endorsement, the relevant issue is how it would be perceived by an objective observer, acquainted with the text, legislative history, and implementation of the statute.”); Santa Fe Independent School Dist. v. Doe, 30 U.S. 290, 308 (2005) (“In cases involving state participation in a religious activity, one of the relevant questions is whether an objective observer, acquainted with the text, legislative history, and implementation of the statute, would perceive it as a state endorsement of prayer in public schools”) (internal citations omitted).

[9] See generally, Memorandum from thePublic Rights/Private Conscience Project to Interested Parties, Proposed Conscience or Religion-Based Exemption for Public Officials Authorized to Solemnize Marriages (June 30, 2015) available at http://web.law.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/microsites/gender-sexuality/marriageexemptionsmemojune30.pdf. The fact that the discrimination is permissive rather than mandatory is not dispositive; like the students’ religious speech in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, the decision of the state to permit such religiously-motivated conduct by government employees on government property in the provision of government services is “clearly a choice attributable to the State.” Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290, 311 (2000).

[10] See Kaoma, supra n. 2, and Kapya Kaoma, Colonizing African Values: How the U.S. Christian Right is Transforming Sexual Politics in Africa, Political Research Associates, 2012, http://www.politicalresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/Colonizing-African-Values.pdf.

[11] The Center for Constitutional Rights represents Sexual Minorities Uganda, a coalition of Ugandan LGBTI groups, in its challenge – based on international legal protections against group-based persecution – to a right-wing Christian evangelical from the U.S. who played a key role in the dramatic expansion of severe discrimination against LGBTI people in Uganda. Sexual Minorities Uganda v. Scott Lively, http://ccrjustice.org/home/what-we-do/our-cases/sexual-minorities-uganda-v-scott-lively. In its August 14, 2013, ruling allowing the case to proceed, the Court held that “[w]idespread, systematic persecution of LGBTI people constitutes a crime against humanity that unquestionably violates international norms.” Sexual Minorities Uganda v. Lively, 960 F. Supp. 2d 304, 316 (D. Mass. 2013).

[12] Prosecutor v. Kupreskic, Judgment of the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia, Case No. IT-95-16-T, Judgment, ¶751, January 14, 2000, http://www.icty.org/x/cases/kupreskic/tjug/en/kup-tj000114e.pdf.

[13] Church and State: Tony Perkins on Trump and the Johnson Amendment, CNN, January 30, 2017, https://youtu.be/AMEI9NpAQM8.

[14] Kentucky Clerk Kim Davis Denied Marriage Licenses for Her Friends, ABCNews, September 22, 2015, http://abcnews.go.com/US/kentucky-clerk-kim-davis-denied-marriage-licenses-friends/story?id=33939041.

[15] Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205, 220 (1972).

[16] 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000bb - 2000bb-4

[17] 461 U.S. 574, 604 (1983).

[18] On February 20, 2015, the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) – a private entity that received over $34 million in grants and contracts from the federal government in 2016 – wrote to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) on behalf of a coalition of FBOs that are existing and/or prospective grantees, contractors, sub-grantees or subcontractors of ORR grants to provide services to unaccompanied migrant children. The USCCB expressed a religious and moral objection to ORR programs that include services designed to prevent, detect, and respond to sexual abuse involving unaccompanied minors. Specifically, it objected to a provision of the program that beneficiaries of ORR-funded programs be provided access to emergency contraception and information about all lawful pregnancy-related medical services, including abortions. Letter from U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, Nat’l Ass’n of Evangelicals, World Vision, Inc., Catholic Relief Servs. and World Relief to Elizabeth Sohn, Policy Analyst, Division of Policy, Office of Refugee Resettlement, Admin. for Children & Families (February 20, 2015), available at http://www.regulations.gov/#!documentDetail;D=ACF-2015-0002-0024.

[19] Martin Lederman, Why the Law Does Not (and Should Not) Allow Religiously Motivated Contractors to Discriminate Against Their LGBT Employees, Cornerstone (July 31, 2014), http://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/responses/why-the-law-does-not-and-should-not-allow-religiously-motivated-contractors-to-discriminate-against-their-lgbt-employees.

[20] 134 S. Ct. 2751 (2014).

[21] 136 S. Ct. 444 (2016).

[22] For a list of states with state laws that would be preempted by such a provision, see Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives, Guttmacher Institute, February 1, 2017, https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/insurance-coverage-contraceptives.

[23] Tim O’Neil, Missouri legislator files suit to be exempted from contraception mandate in state health plan, Stl Louis Post Dispatch, August 14, 2013,

www.stltoday.com/news/local/metro/missouri-legislator-files-suit-to-be-exempted-from-contraception-mandate/article_911b75c9-8004-55be-9a76-44c0fa637e02.html

[24] 42 USC 2000e-1(a).

[25] 42 USC 12113(d).

[26] H.R. 2802, 114th Congress (2015-2016), https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2802/text.

[27] Issues of Importance to Catholics, Trump-Pence Campaign, September 22, 2016, https://www.donaldjtrump.com/press-releases/issues-of-importance-to-catholics.

[28] See Texas Monthly, Inc. v. Bullock, 489 U.S. 1 (1989). In Texas Monthly, the Supreme Court struck down a tax exemption offered exclusively to religious publications, in part because the exemption shifted costs onto non-beneficiaries. The Court explained that “every tax exemption constitutes a subsidy that affects nonqualifying taxpayers, forcing them to become ‘indirect and vicarious donors.’” Texas Monthly, at 14.

[29] Jeremy W. Peters, Obama’s Protections for LGBT Workers Will Remain Under Trump, New York Times, January 30, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/30/us/politics/obama-trump-protections-lgbt-workers.html?_r=0.