|

|

|

|

Trouble seeing this email? Read in your browser.

In This Issue:

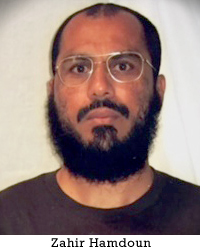

Gitmo “forever prisoner” cleared for release“I have become a body without a soul. I breathe, eat and drink, but I don’t belong to the world of living creatures. I rather belong to another world, a world that is buried in a grave called Guantánamo.” Those are the words of CCR client Zahir Hamdoun describing his experience being held at Guantánamo without charge since 2002, when he was 22 years old. Mr. Hamdoun had been among Guantánamo’s so-called “forever prisoners” slated for indefinite detention— those prisoners who were not cleared for release, but most of whom the government has no intention of charging. On Tuesday, that changed. Mr. Hamdoun was cleared for transfer by a Periodic Review Board (PRB). Clearance by the government is a step in the process of getting released from Guantánamo, and Mr. Hamdoun’s clearance is welcome news. However, it is hardly sufficient. Of the 93 men still detained at Guantánamo, 35 are cleared for release, many of them for years. Among those men are CCR clients Ghaleb Nasser Al-Bihani, Mohammed Al-Hamiri, Tariq Ba Odah, Muhammadi Davliatov, and Mohammed Kamin. For being cleared to mean anything, it must lead to actual release.

Opposing torture on death rowLast Tuesday, CCR joined the National Religious Campaign Against Torture (NRCAT) and Reprieve U.S. on an amicus brief urging the U.S. Supreme Court to review the death penalty case of Bobby James Moore. Moore has been on death row since 1980, when he was 20 years old, and has spent the last 15 years in solitary confinement (which is standard practice on death row in Texas). The amicus brief argues that prolonged solitary confinement awaiting execution violates Eighth Amendment prohibitions on cruel and unusual punishment. CCR has previously argued that the time awaiting execution and conditions on death row amount to torture, in our report “The United States Tortures Before It Kills: An Examination of the Death Row Experience from a Human Rights Perspective.” We have also collected extensive evidence, in our successful challenge to long-term solitary confinement in California, showing the devastating effects of the practice on both mental and physical health. CCR is unequivocally opposed to the death penalty, and we support efforts to abolish it entirely. Until then, people on death row must be protected from abuses like prolonged solitary confinement. We hope the Supreme Court will take this case and make the right decision. CCR at 50: Challenging executive war powerOf course, the power to declare war belongs not to the president, but to Congress. Yet, as former CCR Vice President Peter Weiss noted, “Presidents have mostly taken the position that [the commander-in-chief power in the Constitution] enables them to decide which wars to fight, which is absolutely wrong and clearly not what the founders intended.” That’s one reason CCR has repeatedly challenged executive war-making. In 1975, CCR filed Drinan v. Ford in an effort to stop military operations in Cambodia. Then, in 1990, during the first Gulf War, we challenged President George H.W. Bush’s attempt to declare war unilaterally without congressional authorization in Dellums v. Bush. The case was notable for its rare consideration of whether the federal courts have jurisdiction over the War Powers Clause of the Constitution, and for the court’s ruling that they did. CCR has continued to challenge to expansive claims of executive war powers today, notably in our efforts to halt the targeted killing program. This work has included our lawsuits on behalf of the families of U.S. citizens – including a 16-year-old boy – killed by U.S. drone strikes in Yemen. Beyond the legal claims, this work sought to challenge the expanding notion of global war, where the battlefield becomes wherever the president unilaterally decides to fire missiles or seize and hold suspects without charge. In addition to our litigation seeking to curb U.S. militarism, CCR has consistently been an anti-war voice, speaking out against warmongering and demanding reparations for the victims of war crimes. |